Hard, harder, hardest: Where are we in the cycle?

0 January 29, 2020 at 3:31 pm by Glenn McGillivrayIn this piece, industry veteran Phil Cook makes a number of good points about the current state of the p&c market in Canada. Cook makes the distinction between a hard market and a difficult market, sharing that he is not yet convinced that we are currently in the thralls of the former.

He notes: “Hard markets are really only properly identified with benefit of hindsight. It is very difficult to say in the first year of a hard market that you’re in a hard market, because it only really becomes apparent after one, two or three years that this is the beginning of a hard market. By 2022…we can look back and say, ‘Yes, it was a hard market’.”

He makes a good point. When you are on top of a mountain, you know you are on top – you just have to look around. But because of the relative nature of the term, you won’t know if you are in a hard market until after the fact. The term ‘hard’ is a comparative, and all information has to be in before any final determination can be made.

This is why those in the know are deferring the pigeon hole of “hard market”, opting instead to use such adjectives as hardening, firming, correcting, turning and realigning.

He continued; “Is it a hard market or is it just a difficult market? My personal opinion right now is that it’s a difficult market and it may well just be a correction in a market cycle.”

While a hard market is a difficult market, a difficult market is not necessarily a hard market. There is hardening and there is hard (with the later being a superlative) but we won’t know where we are until after the fact. Of course, there is no hard [pardon the pun] and fast definition of a ‘hard’ market, and this absence adds another layer of uncertainty to the matter.

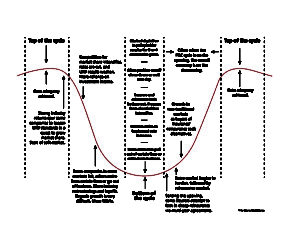

In a presentation given at the Insurance Institute of Canada’s Industry Trends & Predictions: 2020 breakfast held in Toronto January 16, Cook provided his take on the typical industry market cycle:

Hard and soft markets are not the same as market cycles, Cook said in his presentation. The industry is always in the middle of market cycles, which tend to last about three to five years in North America. There’s no middle ground in market cycles – they are going one way or another.

Hard and soft markets are very, very different, he said. “We tend to think of hard and soft markets the same way as we do market cycles, in that as soon as the hard market is over, we’re in a soft market. Or while we’re in a soft market, and it changes, we’re immediately in a hard market. That is absolutely not the case,” Cook said, noting there are extensive periods in between hard and soft markets when it’s just a regular, or (relatively) stable, market.

My take on the cycle is that it behaves like a wavy continuum, with the crest of the wave being the hard market, the lowest point being the soft market, and everything else being the various stages in between. Cook is right that the market isn’t binary, it doesn’t just flip from hard to soft and vice versa like a light switch. There is normally a multi-year transition between the two, where the market is either leading to or away from a hard market and away or to a soft market, with relative periods of stability in between.

The graphic here, which I created for a CU piece some years ago and was published with permission in the Financial Times of London’s Reinsurance Survey the day after 9/11, was meant to be an archetype of the mechanics of the insurance cycle (i.e. a show of general tendencies) and not exactly representative of how things play out each and every time. Every market cycle is different in some way or another.

This graphic was part of an article I wrote about the insurance cycle titled What Comes Around…(July 2001). I have parked a PDF of the article here for anyone that may be interested in reading how the insurance cycle used to work. With the latest soft cycle lasting an unprecedented decade-and-a-half-plus (Zurich Insurance commented that it hasn’t seen the current market since about 2002), it may be safe to say that market cycle dynamics of the past are all but dead.

Indeed, this latest market correction seems to be a fair bit different than anything we have seen in the past, and this is where my and Cook’s concurrence begins to diverge a little.

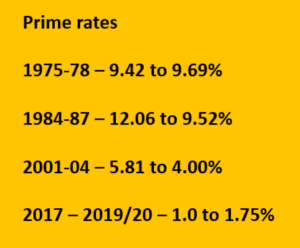

Cook, who has been involved in the Canadian p&c sector since 1967, maintains that he has only seen three hard markets in his career: 1975-78, 1984-87 and 2001-04.

He doesn’t believe we are currently in a hard market because neither of the main indicators – combined ratio and return on equity – are showing that we are quite ‘there’:

“Combined ratios leading up to the last hard market in 2001 were 105.9% in 1999, 108.7% in 2000 and 111% in 2001. Three years in a row of massively increasing 100+ combined ratios. Also, return on equity (ROE), a measure of insurers’ profitability, was tanking. ROE was 6.3% in 2000, 2.6% in 2001 and 1.7% in 2002. By comparison, the combined ratios for the industry stood at 96.6% in 2017 and 98.6% in 2018. P&C results for 2019 are not in yet, but extrapolating based on third-quarter actual results (99.93% combined ratio), “it’s almost certain that we will have a combined ratio in excess of 100; most likely in the 102-103% range.”

This is where I have a bit of a problem with Cook’s argument, largely because of today’s vastly different interest rate regime. Essentially, the 110 combined ratio goalpost has to be moved.

This is where I have a bit of a problem with Cook’s argument, largely because of today’s vastly different interest rate regime. Essentially, the 110 combined ratio goalpost has to be moved.

The differences between interest rates then and now are considerable. Essentially, low interest rates mean that the ~100 combined ratios of today are the ~110 combined ratios of the past. So we are, in effect, already ‘there’ with regard to the kind of high-trending combined ratios that help push the firming of insurance markets.

Of his second indicator, return on equity, Cook notes: “Likewise, if you look at ROE, it was 7.3% in 2017, 4.6% in 2018, and it’s projected to be about 4.3% in 2019. So while the current market “has similar attributes, it has nowhere near the severity of the previous ones,” Cook said.

Cook’s remarks about consecutive years of tanking ROEs is well taken.

In the case of the first three of Cook’s career hard markets, ROEs were weak at the start but improved dramatically by the end of the stated period – likely largely due to increased premiums and deductibles. This, however, isn’t the case with the current market turn, though, as ROE began rather weak and is weakening further, dropping almost 3 points from 2017 and 2018 and projected to dip a bit further still for 2019. So is this the sign of a hardening market or, perhaps, something else?

We do have to keep in mind one thing when comparing present day ROEs to those of the past, particularly the distant past: The way in which unrealized gains are now put in the books has changed quite significantly due to the implementation of IFRS in 2010/11. Comparing contemporary ROEs with those posted prior to IFRS would no longer be apple to apples.

Conclusion

Are we in the grips of a hard market, a hardening market or something else? Effective arguments might be made on all sides, though hopefully everyone can agree that we don’t have enough information to make an absolute determination right now.

But one thing may be obvious – we might be in the midst of one of the strangest – if not the strangest – market ever. And I believe that what we are currently experiencing might merely be a preview of how we can expect markets to play out going forward.

Back in the day, the tide seemed to rise or sink all boats. That is, the market for all major lines of p&c insurance seemed to go up and down in fairly close tandem, like a monolith. Though each of the lines had its own sub-dynamics going, capital was capital, and it was deployed or re-deployed in basically the same way and at the same (slow) speeds across all major lines.

But now, we have a much more robust and finely-tuned ability to analyze results in a very granular fashion thanks, in large part, to sophisticated finance, actuarial and capital models, and allocate/reallocate capital faster and in a less reactionary way than in the past (invisible but formidable competitive market forces notwithstanding).

Today, this ability more resembles a finely-honed surgical laser than the blunt instrument it once was.

Hence, the market is difficult, but only for some accounts, for some lines, in some places. Sweeping across-the-board market corrections may be a thing of the past. The market, as Guy Carpenter describes in its look at January 2020 reinsurance renewals, is “asymmetrical” or, as Willis Re has called it in its annual review, divergent.

Rather than a rising tide lifting all boats, it now depends on where the boats are in the locks or whether they are even in the canal at all.

Whether this can even be considered a hard or hardening market is, as far as I’m concerned, still up in the air.

Epilogue

With this piece being too long as it is, here are just a few observations about current market conditions, including how today’s market differs from those of the past:

- Changes to the market began on the casualty side in the second half to fourth quarter of 2018, driven greatly by significant capacity reductions and price increases/firming of terms in certain lines. These changes largely originating from the London market.

- Changes to property came later and seem not to be marked by similar capacity reductions, at least not for the most part. Places like Florida and parts of California are marked for significant rate increases and firming in contract terms.

- As strange as it sounds, increases in property, particularly property cat, may not be driven by cat losses as much as some have opined. Florida and California (and, perhaps, Japan) aside, property may just be getting pulled along for the ride (though by all rights, the segment should have firmed some time ago). The segment is still marked by massive amounts of surplus capital (including both traditional and non-traditional reinsurance capacity), which is muting needed price increases, and that won’t change overnight. We will see what happens at April 1 and July 1 renewals this year.

- Rate-on-line for property cat is still severely depressed, with rates being nowhere near levels seen in the past and not where they need to be, surprising given back-to-back large-loss years (2017 and 2018) that, historically, would have moved markets almost overnight.

- After unprecedented back-to-back wildfire loss years in 2017 and 2018, substantial price increases in California could be skewing premium increase data for all of the U.S. It would be interesting to see how much personal property premiums have increased in the U.S. without California included in the data.

- Past market corrections have often been top down, i.e. pushed down from retrocessionaires to reinsurers to primary companies. This time, there are reported to be sizeable price increases in retro markets (which are difficult to quantify and confirm due to the black box nature of that segment) and significant price and contract term changes in primary markets, but the reinsurance segment appears to be lagging, particularly on the property cat side.

- Prices and deductibles for some Canadian condo accounts (for the most part, those with significant loss experience) are going up, in some cases quite dramatically. This is happening across the country and is not the result of a single loss event in a single place.

- According to work done by IBC some years ago, the typical Canadian p&c market cycle lasted about seven years from peak to peak. Looking at the most recent soft cycle, this has clearly changed.

Note: By submitting your comments you acknowledge that insBlogs has the right to reproduce, broadcast and publicize those comments or any part thereof in any manner whatsoever. Please note that due to the volume of e-mails we receive, not all comments will be published and those that are published will not be edited. However, all will be carefully read, considered and appreciated.

Leave a Reply