Far and wide

0 February 2, 2023 at 12:13 pm by Glenn McGillivrayLarge storms like the kind we saw in 2022 can present unique challenges to Canadian insurers

Storm damage on Merivale Road at Viewmount Drive caused by the May 2022 Derecho that struck the city of Ottawa. (Josh Robillard – Wikkimedia Commons)

Preliminary numbers for 2022 Canadian insured disaster losses are in (or out), and they’re not pretty.

According to Catastrophe Indices and Quantification Inc. (CatIQ) 15 declared events classed as ‘cats’ (i.e. each driving losses of a minimum of $30 million insured, up from $25 million previously) resulted in preliminary insured losses of $3.1 billion.

This places the year in the top three costliest on record, with 2016 (the year of the Fort McMurray wildfire and other events, ~$5 billion insured) and 2013 (the year of the Southern Alberta and Toronto floods and other events, $3.1 billion insured).

Both 2013 and 2022 have been rounded up. None of the figures include loss adjustment expenses.

According to a CatIQ release “[T]wo events made up a substantial portion of the overall industry total – the May 21 derecho in Ontario and Quebec ($1 billion) and Hurricane Fiona in Atlantic Canada in September ($800 million).”

The pair are now included in the top ten costliest weather events in Canadian insurance history.

The year marks only the second time the country has experienced two billion-dollar events (economic) in the same year, after the two major floods in 2013.

Three events experienced in Canada last year shared an important attribute, one which I would like to focus on here – size.

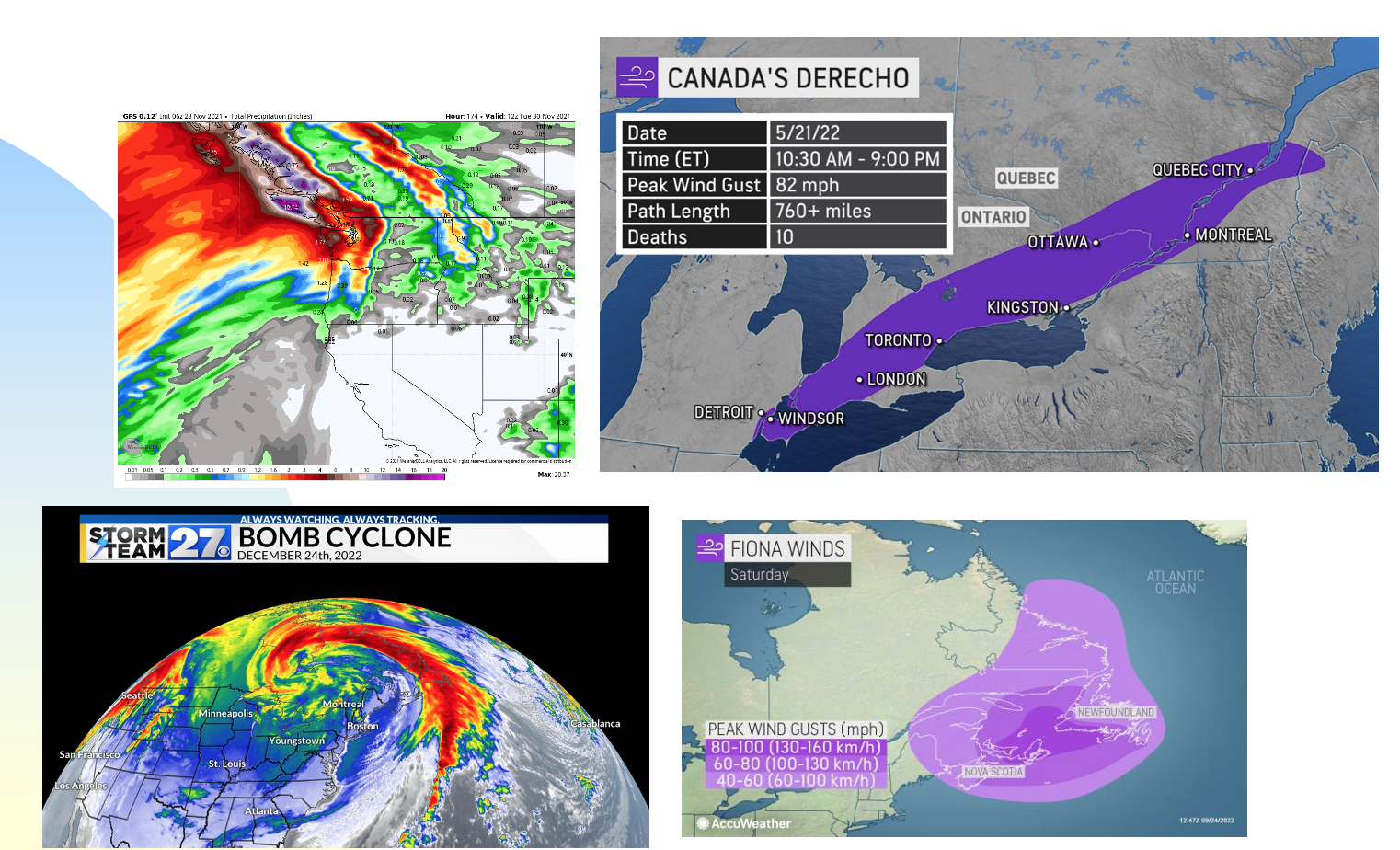

The derecho in Southern Ontario/Southern Quebec in May, post tropical storm Fiona in September and the bomb cyclone close to Christmas were all spatially massive storms with huge damage footprints – even moreso when including the US side.

The May derecho spanned some 1,000 kilometres in length when considering both the US and Canadian portions. Looking at Canada alone, there was damage reported along an 800 kilometre-long tract, with several major Canadian urban centres being impacted, including Windsor, London, Hamilton, Burlington, Oakville, Mississauga, Toronto, Pickering, Whitby, Oshawa, Kingston, Ottawa, Montreal and Quebec. The region impacted by the storm is responsible for generating about a full quarter of the country’s GDP. Close to 63,000 claims were filed as a result of the event.

Post tropical storm Fiona made landfall between Guysborough and the Canso area of Nova Scotia on the evening of September 23 and into the early hours of the 24th ripping through large portions of Cape Breton Island before moving on to Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador. Damage from the storm was extensive, with roofs blown off buildings; trees down on houses and vehicles; piers, ports and boats destroyed; and structures washed out to sea. Critical public infrastructure, such as roads, bridges and culverts, also took a beating. Power outages were extensive, with 400,000 customers without electricity in Nova Scotia and almost all of PEI in the dark by the morning of the 24th. Close to 36,000 claims were filed as a result of the event.

The bomb cyclone was described by CatIQ as “An expansive, rapidly intensifying low pressure system, [which] passed through southern Ontario, southern, Quebec, and the Maritimes between December 22 and 25. Prolonged powerful sustained winds and gusts drove blizzard conditions, toppled trees and power lines, and caused coastal flooding. Power outages were prolonged in some areas, leaving customers in the dark for more than a week in some cases.” Close to 20,000 claims were filed as a result of the event resulting in preliminary insured damage of $180 million (CatIQ).

A couple of other recent events also fit the bill for inclusion in this discussion.

The November 2021 atmospheric river event in the Pacific Northwest hit widespread areas of southwestern BC with extreme rains and resultant rock and mudslides. According to a study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the flooding may have led to almost $5 billion in economic damages. Insured damage came in at more than $675 million (CatIQ).

In early May, 2018 a massive windstorm with gusts of up to 126 km/h whipped across Southern Ontario and Southern Quebec, essentially leading to a large number of relatively small damage claims (in most cases). Close to 72,000 claims were filed as a result of the event, leading to insured damage exceeding $600 million (CatIQ).

Nov 2021 atmospheric river in BC (top left), May 2022 derecho (top right), Dec 2022 bomb cyclone (bottom left) and post tropical storm Fiona Sept 2022 (bottom right).

Storms with these kinds of damage footprints can present a unique challenge to insurers, particularly smaller, regional carriers.

Along with their potential to overwhelm insurers from a claims adjusting/management and restoration perspective is the issue of accumulation management.

While accumulation management is always important (an overconcentrated carrier can get itself in trouble if it writes a lot of business in a small geographical area), even companies that are really good at watching this risk can take a bad hit when a large storm sweeps through an insurer’s area of operation.

The hit can be lethal.

As a result of the derecho, one very small company in Ontario was rumoured to have received claims valued at more than twice the company’s annual premium volume. It was saved by a stop loss reinsurance agreement that it had in place. Another smaller, regional player in Eastern Canada was reported to have received about 300 claims an hour in the days following Fiona.

This threat underscores the need for a robust, well-crafted cat reinsurance program.

From a loss control perspective, four out of five of the storms mentioned above featured extreme wind as a major source of damage.

ICLR has been advocating for some time now that new homes in Canada be built with extreme wind in mind and has been working with building codes officials, home builders and others to this end. The building industry often pushes back with the argument “Why build for tornadoes when they are so localized and relatively rare.”

Our retort is that we have to build with extreme wind in mind, and while that includes tornadoes of up to EF2 in rating, it may also include other forms of extreme wind.

These large storms nullify arguments that we shouldn’t build for wind because only select areas (of Ontario, for example) are at risk.

We know this just isn’t the case.

Note: By submitting your comments you acknowledge that insBlogs has the right to reproduce, broadcast and publicize those comments or any part thereof in any manner whatsoever. Please note that due to the volume of e-mails we receive, not all comments will be published and those that are published will not be edited. However, all will be carefully read, considered and appreciated.

Leave a Reply