Flood apparently trumps fire

1 March 27, 2017 at 1:56 pm by Glenn McGillivray The Fort McMurray wildfire will end up costing government (read: taxpayers) and insurers considerably more than the flooding in southern Alberta in 2013. However, it appears to be the flood that is having – and will continue to have – the longest lasting impact on public policy and the insurance industry of the two.

The Fort McMurray wildfire will end up costing government (read: taxpayers) and insurers considerably more than the flooding in southern Alberta in 2013. However, it appears to be the flood that is having – and will continue to have – the longest lasting impact on public policy and the insurance industry of the two.

This is for a few reasons.

Overland flood the most common peril

Overland flood is the most common peril in Canada (indeed, it is the most common peril in most western developed countries). Of the close to 800 meteorological/hydrological and geophysical events captured in the Canadian Disaster Database (1900-present), close to 40% are overland floods.

Each year in the country, overland flooding causes significant damage to public infrastructure and private property, and disruption to business, and climate models indicate that extreme rainfall will likely become more severe and frequent in the future.

Wildfire, on the other hand, while very common in Canada, seldom impacts large communities. Prior to Fort McMurray only two major fires led to any significant property loss and disruption – the 2003 wildfire in Kelowna, BC, and the 2011 wildfire in Slave Lake, Alberta.

Major Wildland Urban Interface fires were so rare in Canada that insurers and others labelled both Kelowna and Slave Lake as ‘one off’ events (which might make sense for Kelowna, but not for a second event just eight years later).

Most government disaster assistance payouts are for floods

Historically, the vast majority of federal government disaster assistance paid out to the provinces (and to citizens via the provinces) has been for flood, as most other perils are insurable in the private market.

And the costs associated with flood are projected to increase.

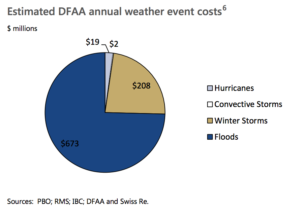

According to a February 2016 Parliamentary Budget Office report, over the next five years, the DFAAs  can expect costs of $229 million a year because of hurricanes and storms, with floods adding another $673 million, for a total of $902 million a year.

can expect costs of $229 million a year because of hurricanes and storms, with floods adding another $673 million, for a total of $902 million a year.

According to the report, DFAA payments related to the 2013 southern Alberta flood event were “expected” to total $1.347 billion. For Fort McMurray, the federal government committed $300 million in DFAAs shortly after the disaster, a significant difference given the Fort McMurray wildfire cost insurers more than twice what the floods cost.

The large gap between the two largely reflects the insurability of fire over flood (fires are heavily insured events in Canada while floods are not, and were even less so in 2013 when no overland flood insurance was available in Canada).

Nothing gets a government’s attention and spurs it to action more than having to make a large, unplanned payout for a disaster, particularly at a time when the federal budget was being cut as the government was entering into a period of austerity, as the federal government was at the time of the 2013 Alberta flood.

Insurance industry paid out more for Alberta than it should have

Though impossible to quantify and prove, Canadian property and casualty insurers likely paid out considerably more in claims for the Alberta flood than they contractually were obligated to given typical coverages and policy wordings.

Ultimately, when faced with thousands of flood damaged basements, claims adjusters often find it nearly impossible to distinguish between backup from a pipe or fixture (normally covered), seepage (sometimes covered) and overland flood (not covered in 2013). When faced with such a dilemma, adjusters will err on the side of caution, default to sewer backup as the cause, and pay the claim. According to anecdotal information, this commonly occurred after past flood events in Canada, like in Peterborough, Ontario in 2002 and 2004.

Two or three companies that had policy wordings that were different than most other companies were widely panned in the press after reports of claims being denied. These companies rapidly changed their positions and paid up.

While there are many claims challenges being faced in Fort McMurray to be sure, fire is usually more straightforward than flood, so there would not be the same questions regarding pay/don’t pay.

The fact that companies paid out many claims or portions of claims without collecting corresponding premium, in my mind, led – at least in part – to the rise of overland flood coverage in Canada.

More being done about the long term challenges associated with flood than wildfire

On March 9, Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale, at the Fifth Regional Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction in the Americas held in Montreal, released the Federal Floodplain Mapping Framework. The Framework is the first in a series of planned Floodplain Mapping Guidelines to be released by the federal government to help reduce flood risk and associated costs in Canada.

The move marked just another in a long list of actions taken by various levels of government, including several Alberta municipalities, the Province of Alberta and the federal government, to address the issue of flood risk. Actions taken over the last few years also include several major mitigation projects, buyouts of flood-prone properties, flood mapping initiatives, building code and land use planning changes, and the launch of the federal National Disaster Mitigation Program. And chances are a healthy portion of the $2 billion Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund announced by the federal government in the March 22, 2017 budget will likely go to flood prevention infrastructure.

Flood-related initiatives from the insurance sector include the hosting of several flood conferences, a number of modelling and mapping initiatives and the launch by more than a dozen companies of overland flood insurance.

All-in-all, billions are being spent by all levels of government across the country to mitigate flood risk. However the annual budget for provincial FireSmart programs is paltry in comparison.

On the wildfire side, nowhere near the same reaction has been triggered.

This isn’t to say that nothing has been done. Since Fort McMurray, the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers has committed to revisiting and updating the 2005 Canadian Wildland Fire Strategy (CWFS). In 2016, the CCFM published Canadian Wildland Fire Strategy: A 10-year Review and Renewed Call to Action and has indicated that in 2017 efforts will be made by the CCFM, the Canadian Interagency Forest Forest Fire Centre and NRCan to update the strategy.

But overall, aside from the recovery and rebuilding efforts in Fort McMurray and the work being done by a few communities that don’t want to be the venue of the next wildfire disaster, the May 2016 Fort McMurray event has not triggered the same degree of soul-searching, reforms and other changes that the 2013 flooding has.

Essentially, a nexus was forged in 2013 between the federal government wishing to get out of the disaster assistance business and the Canadian insurance industry ready to get into flood insurance.

No such perfect storm was triggered by Fort McMurray.

Note: By submitting your comments you acknowledge that insBlogs has the right to reproduce, broadcast and publicize those comments or any part thereof in any manner whatsoever. Please note that due to the volume of e-mails we receive, not all comments will be published and those that are published will not be edited. However, all will be carefully read, considered and appreciated.

What a good use of words in the headline! ‘Trump’ and ‘fire’ is great click bait to get readers off the more common topic associated with those words.